If you have ever visited southern Spain and ventured into one of the numerous small white villages of Andalusia, you may have been surprised to suddenly come across a flight of steps where the road should be, or a sudden sharp right-angled turn. Maybe you were walking along and the road narrowed from three metres to one metre for no obvious reason, and you heave a sigh of relief that you parked your car at the entrance to the village. These roads were originally never constructed for wagons, but for pedestrians, both human and animal. The lack of wheeled transport in medieval Spain means that you can still find many towns and villages like that in Andalusia today.

When the Moors conquered Spain in the eighth century, they brought with them horses, mules and camels, to use both for haulage and to fight in battle. But they brought no wagons, nor any kind of wheeled transport. Why was that? It was not because people in the Middle East didn’t know about the wheel; they had used it for centuries, for making pottery, irrigating the land, and for haulage. During that time there were wagons and chariots in frequent use, but that was before the camel came along. Once that happened there was no contest between the wheeled oxcart and the camel.

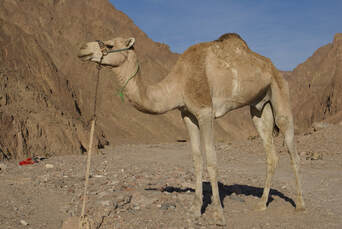

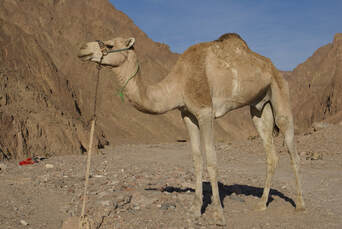

Despite its slow pace, walking at roughly two and a half miles per hour, the camel could cover twenty miles a day for weeks on end without tiring. Even at that speed it was faster and more durable than the plodding ox, besides which the camel could carry between 140 and 230 kg on its back, as much if not more than the oxcart. The camel was also cheaper to maintain and easier to care for than the ox. So ultimately it came down to cash. The pack camel was more efficient and more economical than the slow, lumbering ox. It was also more suited to the dry desert pathways, but to start with, although it was widely used in the villages and nomadic areas of the desert, it wasn’t common in the cities. You may wonder why the medieval Muslim traders didn’t combine both and hitch the camel to a wagon. The simple answer to that was that they didn’t have a suitable harness in the Middle East at that time, not even to allow them to use a horse as a draught animal.

When a new camel saddle was developed, one which allowed the riders more manoeuvrability, nomads became able to fight more effectively and began to dominate the desert caravan trails, and seize control of the long-distance trade routes. Many of the subsequent Islamic conquests were financed by the profits from the camel caravan trade.

Gradually, over the years, the camel became more common in cities and farms; people gave up using their wagons and rented camels from the nomads when they needed transport for haulage. Eventually wheeled transport disappeared altogether and the wagon making industry collapsed in the Middle East and throughout its conquered territories, including Spain. However, as the camel became more popular amongst traders and merchants, they also became more expensive. If people couldn’t afford to buy a camel, or didn’t need to transport their goods over long distances, they would use donkeys and mules, just as they still continue to do in some of the Spanish villages, today.

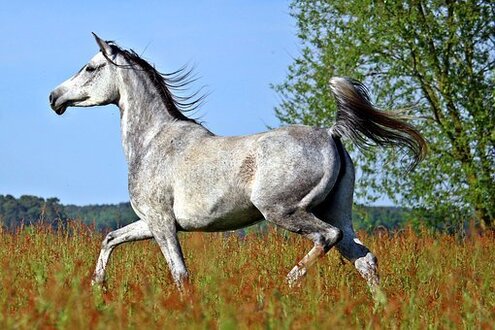

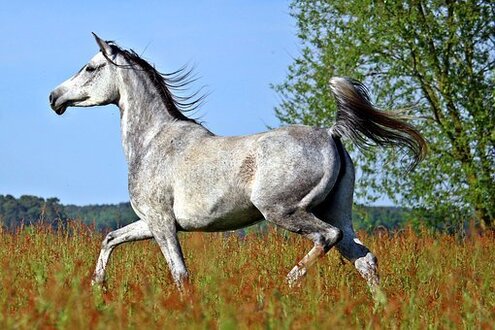

In the same way as the camel was important to nomads and merchants, so the horse was important to the elite Moorish cavalry, and the quality of their horses was greatly prized. The Arabian horse is a distinct breed and one of the oldest in the world, having hardly changed in 4,500 years. It was bred in the desert, in the dry, hot climate of the Arabian peninsula, and because of its exposure to constant sunshine, had a black skin although its coat could be a variety of colours: bay, grey, chestnut, black or roan. These were the horses that the Moors brought with them to Spain; this versatile breed was perfect for the cavalry, being able to travel long distances in hot climates, requiring minimal food and water and with bones that were denser than other breeds and a short back, they could support a heavily armoured horseman with little problem. It was a high spirited animal, with a keen sense of alertness and a good turn of speed.

For centuries, Arab horses had lived closely with their nomadic owners, even sharing their owners’ tents. Because they were so highly prized, it was not surprising that many myths and legends were told about them. One such a legend relates that Mohammed wanted to test the courage and loyalty of his herd, so he set them loose to race towards an oasis, but before they reached the water, he called them back to him. Only five of the horses returned. These loyal animals were said to be the first Arabian horses and all subsequent ones were descended from them.

Whatever the truth of the legends, the Arabian horse is certainly one of the oldest domesticated breeds in existence, and the distinctive features of its head and its high tail carriage have been found carved on Egyptian artefacts from the 16th century BC.

Recent Comments