Traditionally, flamenco has always been associated with Spain and the Roma or gypsy way of life, but in fact there was a similar culture of music and dance in southern Spain a thousand years before the gypsies arrived in Andalusia. The city of Cádiz, known as Gades during the the time of the Phoenicians and the later Roman occupation of the country, was famous for its female dancers who were renowned all across the Mediterranean world for their beauty and sensual dancing. The dancers were often accompanied by musicians and a singer, just as they are today. The ancient works of many Roman writers and historians reveal how popular the Gaditanae, as the women were called, were at the time, and we actually know the name of one of those dancers; she was called Telethusa and she lived in Gades during the first century. And the reason we know about her is due to the poems of the Roman poet, Marcus Valerias Martialis. Apparently he saw her dancing in the market place when he visited Gades and is said to have become infatuated with her, eventually making her his mistress. He was not the only one to write about these sensuous dancers; men, such as the poets Lord Byron and Federico Lorca, the author Cervantes and the historian Richard Ford also wrote about Cádiz and its fascinating Gaditanae.

They describe Telethusa as dancing with her arms above her head, playing the castanets and moving her body to a rhythmic beat. This provocative Oriental style dance was a precursor to flamenco as we see it today.

But the roots of flamenco are more complicated than that. Between the ninth and fourteenth century the Andalusian gypsies, or gitanos as they are known in Spain, migrated to the Iberian peninsula from north-west India. They brought their own culture of Hindu dance and song and with it the instruments that we associate with flamenco dancing: castanets, tambourines, bells and drums. In Andalusia they encountered Christians, Sephardic Jews and Moors, whose cultures were already well established in the land, and over the next five hundred years these cultural influences mingled with their own music. The Moors had brought many musical instruments to Andalusia, including the guitar which Zirab, a Moorish musician, brought from Baghdad in the 9th century. The guitar is the main form of accompaniment for both flamenco song and dance. This inter-mingling of the cultures is what has created flamenco.

There are two distinct parts to flamenco, the song and the dance, and it is the former which sets the character of the performance because it tells the story of the everyday life of the gitanos. The words of the song are then interpreted by the dancer. There are three types of song. Cante Jondo, (deep song) is very emotional and tells of death, despair and longing; it is believed to be the oldest type of cante or song. Then there is the light-hearted Cante Chico (small song) which tells of love and romance, life in the countryside, friendships and fiestas. It is technically a more complicated form of song but far less emotional, and full of humour. Then there is a third style which is a mix of the two and sometimes includes other styles of Spanish folk songs as well, such as the verdiales of the mountain villages. This is called Cante Intermedio. Most of these songs can be traced back many years. Some of them are only sung on certain occasions and it can bring bad luck if they are sung at the wrong time. You can only sing alboreás, for example, at weddings.

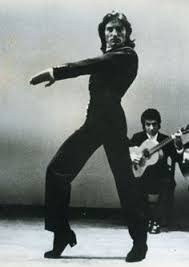

For me the dance is the most spectacular part of flamenco, but of course it would mean so much more to the spectator if they understood the words being sung because the dancer is interpreting them with the movements of her body. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, flamenco songs have been accompanied by the guitar and someone beating time with a small drum or a wooden stick against the ground. While the singer sings stories of love or death, the dancer begins to dance. If the performer is woman, she is dressed in an elaborate long dress, usually with lots of ruffles. Sometimes she wears a gaily decorated shawl which she uses as part of the dance, twirling it through the air or around her body. Or she plays the castanets, their clicking blending with the music and accentuating the beat. She dances sensuously, her arms and hands constantly twisting and turning, in a manner not dissimilar to a classical Hindu dancer, her feet tap and stamp in her high-heeled shoes, their metal caps beating out the rhythm of the music. The male dancer has a more upright style, his back is held erect and his arms and hands mirror those of his partner. When he dances alone his feet do most of the work, performing an intricate style of tap dancing that creates a music of its own. Men dancing in this manner where most of the movement comes from the legs and feet is a style of dance that goes back many years and can be seen in places as far apart as Ireland, the United States and West Africa.

The Golden Age of flamenco was from the end of the eighteenth century until the middle of the nineteenth century. At first it was an outdoor event centred around the family, but in 1842 the first café cantante was opened in Seville. After that many other indoor performances were started in neighbouring cities, but the emphasis was more on the musicians and the dancers; the singer was no longer so important. Many thought that this was downgrading flamenco and a movement was made by influential people such as Federico Lorca and the composer Manuel de Falla to restore flamenco to its pure form. To do this they organised a competition for Primitive Andalusian Cante and succeeded in preventing any further debasement to the original flamenco. That doesn’t mean that the development of flamenco has stood still; many contemporary composers and performers are bringing it to a modern and international audience. And nowadays the Spanish regard flamenco as the music of Spain not just Andalusia.

Below are a couple of books to read if you want to learn more about the origins of flamenco and gypsy culture in Spain: “White Wall of Spain: the mysteries of Andalusian culture” by Allen Josephs “Andalusia: Between dream and reality” by Tony Bryant.

4 Responses

Thank you Joan I have had a black and white pictures of flamenco bought in Spain I have just painted them in colour and am so pleased with them How are you I have been back in UK for a year and hate it Missing Spain and the culture and the locals so much Take care in this weird weather everywhere Love Angela xx

Hi Angela, I can understand you’re missing Spain but it’s probably good to be with your family. Your painting sounds lovely. all the best Joan

Hi Joan

Thx for the shoutout

FYI I just married a sevillana (gorgeous of course) and will move soon to Sevilla I want to be there the rest of my life among the Andalusians and toros and flamencos

Hi Allen, Just come across your message from October last year. Sorry for the delay in replying. It got lost in a load of spam comments to my blogs. Congratulations on getting married and I hope you have a wonderful life in Spain. all the best Joan