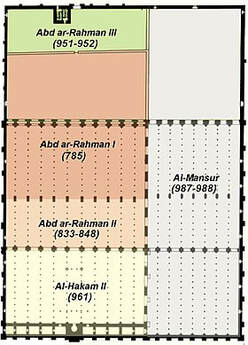

The Mezquita’s fame is widespread, and its history stretches back to the time of the Moors in the 8th century. Work was begun in 785 AD, on the banks of the Guadalquivir, under the orders of Emir Abd al Rahman I. He had bought the site from the Christian community for 100,000 dinars. As was customary in the ancient world, he had chosen a site that already had religious connections; it had been a Visigoth hermitage, before that it was the site of a Roman temple, and from the middle of the 8th century, Christians and Muslims had both worshipped there.

Plan of the Mosque showing when each part was built.

Plan of the Mosque showing when each part was built.

So it wasn’t until after his death, that his son, al Hakam II undertook another enlargement of the mosque in 926 AD. Then finally in 987 AD, al-Mansor, the de facto ruler of al-Andalus after the death of Abd al Hakam, almost doubled the size of the building. Yet, despite so many additions to this magnificent building over a long period of time, the architects managed to maintain its structural unity.

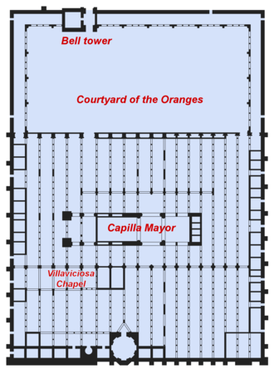

Plan showing the Christian alterations

Plan showing the Christian alterations

First-time visitors to the mosque are amazed to suddenly find themselves in a Christian cathedral. Sadly a lot of the additions to the mosque made by Abd al Rahman II and al-Mansur, were dismantled during the creation of the cathedral.

Further work was done to the cathedral in 1523 under the orders of the Bishop and without the consent of the Cathedral chapter. They tried to stop any further changes by threatening them with the death penalty if they did any more work without Royal assent. So the bishop appealed to King Charles I, who gave his consent.

According to rumour, when the king later visited the cathedral, he is reported to have said: ‘I did not know what this was, otherwise I would not have allowed the old part to be changed; because you are doing what can be done elsewhere, whereas you have destroyed something that is unique in the world.’

A number of organisations, such as the Navarre Heritage Defence Platform are leading the fight to overturn many of these unconstitutional registrations by the Church.

If anyone has any recent news about the ownership of the Mezquita, please let me know.

Recent Comments