When I was writing ‘The Prisoner,’ book three in The City of Dreams series, I decided to introduce a new character, a Christian mercenary, named Jabalah. I based him on the legendary El Cid, known to us all through books and films. But the portrayal of El Cid that legend gives us, is not the whole truth.

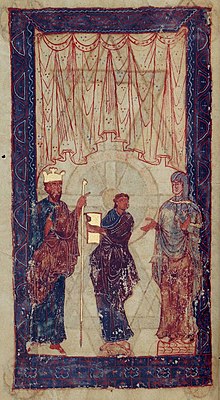

King Ferdinand I of Castille and León

King Ferdinand I of Castille and León

The situation in Spain during the 11th century, was one of chaos and turbulence. The country was split between the Christians in the north and the Muslims in the south, but it was also divided into dozens of principalities, the taifas of the Moors and the rivalling kingdoms and principalities of the Christians, who fought many battles between each other. However, the Christian kings were often happy to make alliances with the Moorish taifas in order to take advantage of their wealth. Alliances of Christian and Moorish armies fought against rival Moorish taifas, as well as upstart Christian princes. The Christians relied on the Moorish gold, and the Moors relied on the extra manpower supplied by the Christian mercenaries. Many Moorish taifas paid a handsome tribute to a Christian king for his protection. One such example was King Fernando I, the most powerful Christian monarch in Spain at that time, having united a large swathe of the north, including Leon and Castile, Galicia and Asturias. He exacted annual tributes from the Moorish taifas of Zaragoza, Toledo, Badajoz and Seville. These enormous bribes enabled the Moors to hold the Christians at bay and prevented the reconquest of Andalucia for many generations.

This was an era of adventurers and paid mercenaries, men with no loyalty to either religion or state, who fought for gold and power rather than king and country. The common image of these men as chivalrous knights fighting for Christianity is a fiction. By and large, they were rough, brutish, uneducated louts, Even their princes lacked education. They were men of the sword and nothing more. The Moors on the other hand, after centuries of civilisation and comfortable living, were a highly cultured and educated people. Their rulers were not only expected to be warriors, but also poets. They were cultured and well educated, but their armies were depleted and they were a poor match for their Christian adversaries.

Many of these mercenaries formed their own armies and served those who paid them the most. Rodrigo Diaz of Bivar was one such mercenary. El Cid as he became known to his Moorish paymasters, got his name from the Arabic, el Sid, or Seyyid, which means simply master. He was an outstanding warrior and his exploits were soon listed in the chronicles of the period as El Cid el Campeador, The Champion, because he particularly excelled in the bouts of one-to-one combat that preceded a battle. It was customary at that time, for the Champion to march ahead of his troops, and challenge the opposing army to send out their own champion. The two men would fight to the death, and the resulting victory would act as a great motivation to the army of the winner. El Cid’s skill as a swordsman soon became legendary.

But who was he really? When we step away from the myths and legends that surround his name, we can see that he had as many faults as virtues. He would fight for the Moors as easily as the Christians, and neither mosques nor churches were safe from looting.

He was first mentioned in 1064, when as a youth in his twenties, he won his title of Champion after defeating a knight from Navarra in a challenge. This victory got him promoted to Commander-in-chief of the Castillian army, serving first under King Sancho, and later King Alfonso. However, by 1081, he had made so many enemies within the court that the king banished him. Such was his common popularity that when he left the city, he took many of his followers with him, and rode directly to the city of Zaragoza and offered his services to its powerful Moorish ruler.

He was first mentioned in 1064, when as a youth in his twenties, he won his title of Champion after defeating a knight from Navarra in a challenge. This victory got him promoted to Commander-in-chief of the Castillian army, serving first under King Sancho, and later King Alfonso. However, by 1081, he had made so many enemies within the court that the king banished him. Such was his common popularity that when he left the city, he took many of his followers with him, and rode directly to the city of Zaragoza and offered his services to its powerful Moorish ruler.

Sorting truth from fiction is never easy, but the further you go back into the past, the more difficult it becomes. It is even hazier with Rodrigo Diaz of Bivar. To the Spanish Christians he was the hero of the age, a brave, gallant leader of men, a magnificent soldier who fought for Christianity against the infidels, and the Champion of Castille. But when the minstrels sang the songs that were written about him, they forgot to mention that he not only fought against the infidels, but also fought with them, and that his only loyalty was to himself.

Recent Comments