My latest novel is set in Spain in 1935, the year before the Spanish Civil War broke out. In the story one of my characters is asked to be the local representative for a new branch of the Sección Femenina—the women’s branch of the Falange movement. As I was writing I was reminded of when I wrote my only non-fiction book, Daughters of Spain. I had interviewed various women about what it was like, as a woman, to live in Spain during the Franco years, when the Falange party had great influence. Below are a few of the things that I was told. But first, a short description of the Falange Party and the aims of the Sección Femenina.

The Spanish Falange was founded by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, son of the right-wing dictator, Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1933. Its aim was to promote a strong, united nationalism within the state and to impose a rigorous discipline on education. It condemned socialism, communism, republicanism and capitalism and promoted fascism, modelled on the Italian fascist state at the time. By 1937 it had become the official party of the Nationalist State in Spain.

The plan of the Falangists was always to return Spain to the days before the Second Republic and central to this plan was the role of women. There was to be a strict divide between the men who were to produce a new nation and the women who were to bear the nation’s sons.

A youth section called Las Flechas was set up and members were urged to participate in physical education and sport; the first rally took place in Seville in October 1938 where 1,600 girls and adolescents gave a display of gymnastics and dancing. However not everyone was happy at the thought of young women participating in sport and the Church spoke out against it. So women were limited to taking part in what were deemed “appropriate sports”, such as swimming, tennis and gymnastics; these were referred to as “beauty sports.” Any sport with a more masculine side to it was discouraged and the emphasis was always on refinement, self-control and modesty—one wonders what view they would take of the current growth in women’s football and Spain winning the World Cup.

José Antonio’s sister, Pilar Primo de Rivera started the Sección Femenina with the aim of teaching women how to be “good patriots, good Christians and good wives.” Most middle-class wives were expected to participate in some sort of social service in the Sección Femenina: helping in canteens, or schools or health clinics and they were encouraged to intervene in the lives of other women and ensure their compliance with the State. At the time the social service was considered to be a war-time necessity but it continued after the war was over and became compulsory. If a woman did not complete her six months social service she was unable to get a passport, a driving licence or receive a university degree. Before undertaking her stint of social service the woman was also expected to do a period of intensive training with a team made up of the leaders of the Sección Femenina, priests and doctors. The women were taught about childcare, housekeeping and other feminine tasks and indoctrinated with anti-liberalist literature. Although Pilar Primo de Rivera wanted women to have training in social work and nursing, her group strongly promoted the idea that women should marry and produce children for “the fatherland.” That was to be their main role in life. A list of required behaviour for new wives was provided; some of which today is truly laughable.

ADVICE ON PREPARATION FOR MARRIAGE

The new wife should observe the following:

Have a delicious meal ready when her husband gets home from work

Remove his shoes

Speak in a low tone

Tidy herself up before he arrives home by doing her makeup, hair etc.

Ensure that there is no noise in the house

Listen, let him speak first

Never complain

Understand his world of tension and stress

Don’t ask for explanations or question his integrity

Don’t discuss her day or her hobbies; they are trivial in comparison

Get ready for bed so as to not keep him waiting

Look her best when she goes to bed

Submit to sex humbly; his satisfaction is more important than hers

Wait until he is asleep before she puts in her rollers, etc.

Then set her alarm so that she can get up early and make him a cup of tea.

I thought you might like to read what some of the women I interviewed had to say about how the erosion of women’s rights affected their own lives.

ARACELI born in Malaga in 1918

‘During the war, I was a Falangista, a youth member of the Falange; at first my job was to sew soldiers’ uniforms. They would bring me the material and all the buttons, badges and epaulets in a packet. I learnt to cut out the uniforms and sew them, but I wasn’t very good at it. Then later I worked in a canteen, serving food to the orphans. In those days it was voluntary service, designed to help the war effort, but later, under Franco, it became compulsory social service for women. It was similar to the military conscription for men, but women only had to work for six months, helping in the orphanages or health clinics or in schools. If you didn’t do it you couldn’t get a passport or a driver’s licence. It lasted until the 1970s.’…. ‘Well, my sister wanted to join the Falangistas as well, but she was too young; you had to be eighteen, so she joined Las Flechas, (The Arrows), a Falange youth group for the under eighteens. She only joined so she could go to dance classes,’ she added dismissively.

When I was younger I liked to go to church because it was a social occasion and I always went with my friends. The priest was very strict. We weren’t allowed to wear any make-up to church or show any bare skin; all the girls had to wear veils. We each had a different coloured veil and we would exchange them, so that each week we could wear a different colour. When it was Semana Santa we would dress up in our best frocks and wear a mantilla in our hair and we would walk to the church barefoot, carrying our best shoes in our hands so they didn’t get dusty. I remember one year our priest’s sister came to visit him during Semana Santa. She was really surprised to see us wearing the mantilla; she had never seen one before.’

DOLORES born in Rio Gordo in 1926

I went to the local school. It was for all the village children, but the boys and girls were kept strictly separated. The girls didn’t really get much opportunity to study; they had very poor education really and were only allowed to stay in school until they were eight or nine. When the time came for my friends and me to leave our teacher told us that we could continue to attend every day, but if the school inspector came we had to stay at home for the day.’

‘It wasn’t until the Act of 1970 that education became compulsory for children from the age of six to fourteen,’ her husband interjected. ‘But even then there were hundreds of children that never learnt to read and write.’

‘Of course the boys were allowed to stay in school longer. My husband was lucky,’ Lola continued, smiling at her husband. ‘His father was quite well off and didn’t want his son to work in the fields like most of the other boys, so he sent him to Málaga to continue his studies.

I used to go to Mass every week; all the women went, but not many of the men bothered. In the church the women sat on the left and the men on the right. All the women had to cover their arms and heads before they went into the church or the priest would send you out. The priest was very important in the village; he, the mayor and the doctor, they were the most powerful people in the community.

JEANNETTE

‘In those days we were unable to divorce so my husband and I separated and it was while we were living apart that I met someone else and I had another child.

This is still difficult for me to talk about; it caused me so much suffering. Well when the baby was born and I went to register her they wanted to put my husband’s name on the birth certificate. I told them that they couldn’t do that because he was not the father. They said if I wanted my name on the birth certificate I also had to have my husband’s name. We argued for a bit then they asked me the father’s name. I told them and they wrote his name in as the father and put the mother as unknown. I told them that it was wrong; that I was the mother, but they wouldn’t listen. How could they put “mother unknown” when I was standing there right in front of them?’

‘You know how in Spain every child has two surnames, the first is the father’s name and the second the mother’s. Well my daughter had both surnames from her father,’ Jeannette explained. ‘Then when she was four years old something even worse happened; her father came and took her away. He had married by then and he and his wife wanted her to live with them. I could do nothing. I had no rights whatsoever over my own child; my name did not appear on any document as her mother. It broke my heart when they took her away.’

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Although there was no great feminist movement in Spain in the 1960s and 70s as there was in other countries, the beginning of the 20th century had its share of feminist thinkers. At that time education for middle and upper-class women began to improve. Women began to fight to break the “iron ceiling”. In 1915 the Residencia de Señoritas opened in Madrid. Most of the women who stayed there were training to be teachers; one of them, María Goyri, was one of the first women in Spain to receive her doctorate. In 1918 the co-educational Instituto Escuela opened with the mandate to widen the range of people’s studies. Then in 1920 the Academia de Jurisprudencia opened its doors to women and began to train them as lawyers.

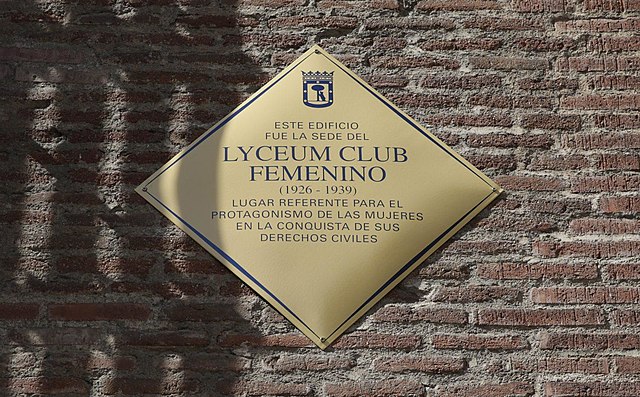

The Asociacíon de Mujeres Españolas (Association of Spanish Women) was established and organised by women of the right-wing aristocracy but it still dealt with very liberal issues such as abortion, the right of women to have jobs in the universities and on the tribunals, salary rights and subsidies for the publication of women’s literature. Then in 1926 María Maeztu, the founder of the Residencia de Señoritas, opened the Lyceum Club Féminino in Madrid. Despite the misogynist protests at the time it became a cultural centre for women to meet and exchange ideas.

In 1925 María Cambrils, a Socialist from Valencia published a book on the freedom of women and in 1927 Margarita Nelken published “En torno a nosotros” about the equality of the sexes. Women were beginning not just to think about equality but to talk and write about women’s rights. With the establishment of the Republic in 1931 women redoubled their efforts to have some changes made. They had the vote and now they made inroads into government. Federica Montseny was named Minister of Health in 1936, the first woman in the world to have a ministerial appointment at that time. More women became involved in politics. This was the period when Dolores Ibárruri, “La Pasionaria” arrived in Madrid as a spokeswoman for the Communist Party and Irene Falcón founded the organisation “Mujeres Antifascistas” (Anti-fascist Women) which was 50,000 strong. In 1936 Matilde de la Torre became a congress-woman for the Popular Front during their short period of government. But it was not easy for women in politics because there was so much resistance from men. The women were the butt of jokes in Parliament and they were under constant scrutiny in both their public and personal lives, especially those who did not have a “normal” life, that is a husband and children. But by 1939 all the reforms that were made during that period had been annulled and many of these intellectual women were banished into exile and oblivion as the Republic fell and Franco took power. Women’s rights became a dream.

The women of Spain had lost two wars: the Civil War and the war of their sex. So I think it right to let one of the interviewees have the last word in this blog.

MARI JESUS

‘Am I happy? Yes, I’m happy with what I’ve done, but truly happy? I don’t know. At least now I make the decisions; first it was my father making decisions for me, then my boyfriend, then my husband; now I make the decisions.’