The beauty of the English language has always been something that has enchanted me. I learnt to read when I was five and haven’t stopped since. Books fascinate me, not just their contents but the feel of them, their smell, the layout of the text, the design of the cover. I would have liked to own a bookshop, but I probably wouldn’t make much money as I would never want to part with any of the stock.

I have a large and motley collection of books which has followed me from house to house each time I have moved, incrementing over the years when I inherited first my mother’s collection of novels and a few months later, my father’s selection of non-fiction which covers everything from politics to the letters of Evelyn Waugh. Add to that all my own books, from childhood, from college, from university, non-fiction, fiction, poetry and you will understand that the main criteria when choosing somewhere to live is, where do I put the books? Throw them out, my well-meaning friends say, you’ve read them. Why keep them? They only collect dust. That one is ancient. Look at the cover; it’s threadbare. This one smells; it’s falling apart. So I reply, ‘Yes, I’ll go through them later.’ And carefully put them back in their box.

Perhaps this is what makes me so sensitive to the changes in our wonderful language that I see almost daily. Yes, I know that language has to evolve but normally its evolution is at a slower pace, so we gradually get used to the new words in our vocabulary and new ways of expressing ourselves. However anyone born before 1960 will have to agree that the world is changing at a much faster pace than ever, certainly since the Industrial Revolution. And if the world is changing then the language must follow suit – new inventions and new ideas need new names, so microchip, blog, social media, website, meme, air fryer, cyber security and thousands of others have come into being. Some new words are easy to understand because they are old words paired together and their new meaning is quite clear. Then there are the words invented by each new generation, a language which is often baffling to their elders. In the sixties we had groovy, dig it, cool, that’s a gas to show our appreciation and what a bummer when things went wrong. In the 70s it was brill and awesome but now I never hear anyone speak like that.

You might be surprised to know that, according to the Global Language Monitor, over five thousand new words are listed in dictionaries each year, and approximately one thousand of them are in English. Many of the changes in language are instigated by young people, which is not surprising because the young want to do things their way, not follow slavishly in the footsteps of their forebears, as did we all once. But quite a few of them go straight over my head. Bussin is one of them. Vaxxed is one that you might presume has come into fashion since the pandemic, but in fact its origin dates back to the 1940s when people were vaccinated to eradicate smallpox and diphtheria. Some such as gaslighting have their origins back in the sixties – in this case from a 1944 film where a man psychologically manipulates his wife – although I don’t remember hearing anybody using it until very recently.

Some new words have come into being in order to highlight unethical behaviour or prejudice. Sports washing is one good example – where a country is permitted to enter its team into a sporting event despite its abuse of human rights. A similar one is Woke a word which is commonplace as the past tense of the verb to wake and has now come into use as an adjective. In fact it was first recorded in African American usage in the late 19th century, meaning awake, but not just in the physical sense, awake to social injustice and discrimination. The contemporary meaning arose in the US during the 1960s, with the idea of being well informed and aware of what was going on in society and was later popularised by association with the Black Lives Matter movement. So not such a new word after all, but maybe more people now want to use it and others are now listening to it.

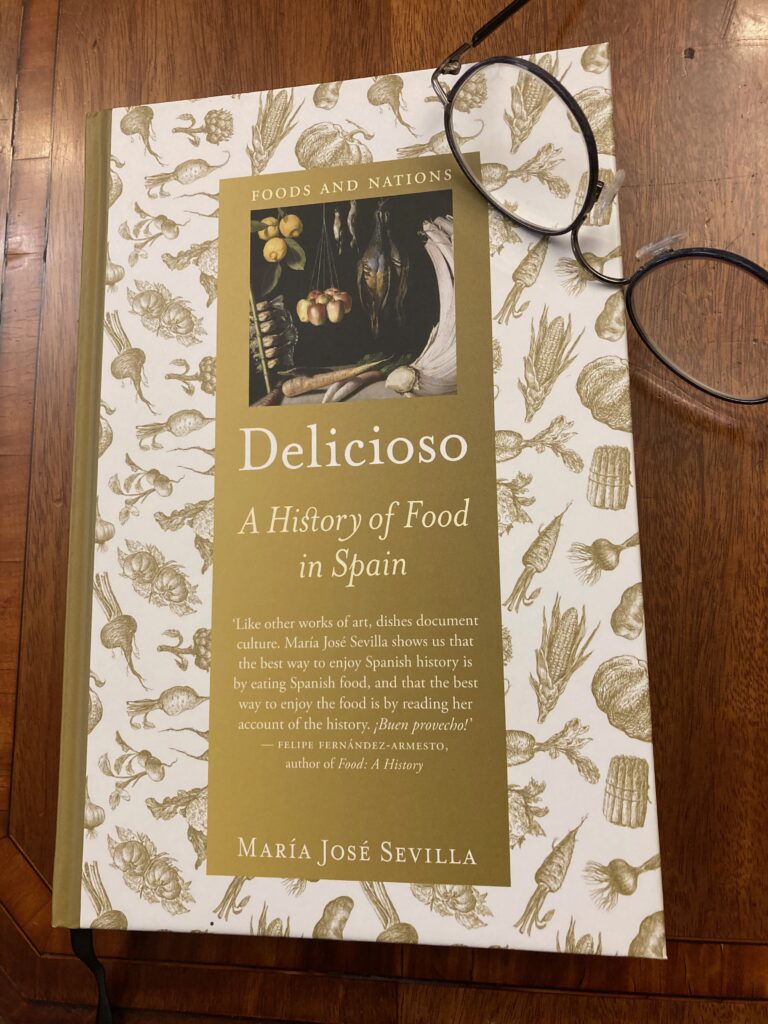

Another thing that has influenced our language is the adoption of foreign words, due I would expect to the increase over the years in foreign travel. Spain in particular has given quite a few words to the English: tapas, siesta, patio, tortilla. And from the French, well it has been estimated that over 30% of English words originate from French, as we might expect as historically England and France have been closely linked for centuries, even before the Norman conquest.

Language changes for many reasons. Sometimes it is as simple as the shortening of a word, gym from gymnasium for example. Sometimes it’s historical, such as the Great Vowel Shift. This is not something I have read about in the history books, but this important change to our language happened between 1400 and 1700 when, for some reason that is still a question of academic argument, the length of the vowels sounds was gradually altered. However this change does offer the hint of an explanation as to why so many words in English have different pronunciations for the same grouping of vowels: bough, though, through, cough, rough, thought, hiccough, lough, thorough, for example.

I was reminded of the movement of language from one country to another the other day, when I heard a Spanish colleague, who doesn’t speak any English, referring to something as buen crack, and he wasn’t referring to cocaine. Obviously the popular Irish word craic for a good time had found its way to Málaga as well as the UK.

Recently, I was recommended a book to read, a contemporary story about an Irish family by a well known author. It was written in English, but I found myself struggling to understand the conversations between the younger characters in the book and wishing that the author had added a glossary to her novel. That was really the moment when I began to feel my age.

Reference: (With thanks to the Linguistic Society of America for their article ‘Is the English Language Changing?’)