In 2012 I read an article in the Economist that stunned me. It was about the children who’d been sent to the British Dominions during, before and even after World War II. These were the child migrants—orphans, neglected or abandoned children. I was amazed, not only that such a thing could happen in Britain but also that it had been kept secret for so many years. If it hadn’t been for a chance circumstance, many of those children, now adults, would never have been reunited with their families. A social worker, Margaret Humphreys, was assigned the case of a woman who claimed that she had been deported from Britain when she was only four-years-old. That was in 1986; since then Mrs Humphreys has discovered that as many as 150,000 children were sent abroad by the British government to start new lives. The last case being as recently as 1970. Director and founder of the Child Migrants’ Trust Mrs Humphreys has worked tirelessly to help these former child migrants find surviving members of their families. Her book EMPTY CRADLES tells of the first seven years of her struggle to bring this knowledge out into the open and to help those involved.

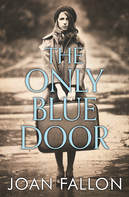

What had surprised me most about the article I read was not just the fact that something like this could happen in Britain but that nobody seemed to be aware of it. I began to read whatever I could find about these child migrants and found that there were a number of books written by the survivors, detailing their lives in orphanages and farm schools—sad stories of miserable lives, slave labour and both physical and sexual abuse—and their long wait to be reunited with their families. This inevitably led me to write a novel–The Only Blue Door—which I published in 2013. Now thirty years after Margaret Humphreys blew the whistle on these events and alerted the world to what had happened, there is an independent inquiry into what, how and why it happened.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse opened at the end of February 2017 and is still investigating and collecting evidence. At the moment they are gathering evidence from three sources: former child migrants, expert witnesses in the history and context of the time, and the Child Migrants Trust who offer help to the survivors. This is all part of the Inquiry’s ‘Protection of Children Outside the UK’ investigation.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries thousands of children were routinely sent out to the overseas British Dominions to start new lives, and this continued during the 20th century until as late as the 1960s. They were taken from orphanages run by religious and charitable institutions and most were despatched to Canada, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Australia. Some were as young as four and five; others were teenagers. Most of the children came from deprived backgrounds and it was considered to be for their own good that they were plucked from poverty and sent to a country where there was good food and new opportunities for them. The receiving countries welcomed them – they needed people, and children were so much easier to mould into their way of life than adults. It also reduced the costs of maintaining destitute children in the UK.

But not all were from orphanages, many children were separated from their families if they were poor or considered to be unsuitable. The children were not given details of their identities and sometimes told, incorrectly, that they were orphans. They were cut off from everyone and everything they knew, even being separated from brothers and sisters. When they reached their destinations some went to private homes, some to orphanages and others—usually the boys—to farm schools. The results were the same. Once in their new homes they frequently lived in harsh conditions, were used as slave labour on farms and as domestic servants and suffered physical and sexual abuse both prior to being sent abroad and after.

But not all were from orphanages, many children were separated from their families if they were poor or considered to be unsuitable. The children were not given details of their identities and sometimes told, incorrectly, that they were orphans. They were cut off from everyone and everything they knew, even being separated from brothers and sisters. When they reached their destinations some went to private homes, some to orphanages and others—usually the boys—to farm schools. The results were the same. Once in their new homes they frequently lived in harsh conditions, were used as slave labour on farms and as domestic servants and suffered physical and sexual abuse both prior to being sent abroad and after.

In 2010 Gordon Brown, the Prime Minister, made a public apology to former child migrants, acknowledging on the part of the British Government that the children were mistreated. Then at long last, in 2017 the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse began. Besides which, the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse is currently holding public inquiries into the responsibilities of the institutions that received the children and the specific allegations of sexual abuse.

Sadly many of the child migrants grew up and died before they could be reunited with their families or return to Britain, and those who are still alive are elderly and sometimes infirm. So the work of the Inquiry is particularly urgent. It may be too late to help some of the survivors, or to punish some of the perpetrators, but at long last the truth will come out.

Britain had been despatching child migrants over a 350-year period. Maybe it was considered acceptable in the 18th and 19th centuries; maybe they truly believed that it was in the children’s best interests, but times change and attitudes change. It is important for people today to know what happened to these children so that it doesn’t happen again—not with British children or any others.

Sadly many of the child migrants grew up and died before they could be reunited with their families or return to Britain, and those who are still alive are elderly and sometimes infirm. So the work of the Inquiry is particularly urgent. It may be too late to help some of the survivors, or to punish some of the perpetrators, but at long last the truth will come out.

Britain had been despatching child migrants over a 350-year period. Maybe it was considered acceptable in the 18th and 19th centuries; maybe they truly believed that it was in the children’s best interests, but times change and attitudes change. It is important for people today to know what happened to these children so that it doesn’t happen again—not with British children or any others.

If you want to read more about this topic I can recommend “New Lives for Old” by Roger Kershaw and Janet Sacks, “Innocents Abroad” by Edward Stokes and Margaret Humphreys’ book “Empty Cradles”.

Recent Comments