Britain’s Sea evacuees: “The child, the best immigrant”

Because children were young and malleable they were seen as the best category of immigrant – easy to assimilate, more adaptable and with a long working life ahead of them. The British Dominions loved them.

Something that only came to light a few years ago was the fact that thousands of children had been sent as child migrants to countries such as Australia and Canada from Britain and never knew their own parents. A social worker called Margaret Humphreys stumbled on this by accident in 1986, when a former child migrant asked her for assistance in locating her relatives. She has since formed the Child Migrant Trust and subsequently helped many people to be reunited with their families.

Throughout the late 19th century thousands of children were routinely sent out to the overseas British Dominions to start new lives, and this continued during the 20th century until as late as the 1960s. They were taken from orphanages run by religious and charitable institutions and despatched to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Some were as young as four and five; others were teenagers. Most of the children came from deprived backgrounds and it was considered to be for their own good that they were plucked from poverty and sent to a country where there was good food and new opportunities for them. The receiving countries welcomed them – they needed people and children were so much easier to mould into their way of life than adults.

So when World War II broke out in 1939 there was already a precedent for sending children abroad to start new lives. June 1940 saw the start of heavy bombing raids across London and, with the threat of an enemy invasion becoming more and more real, it was then that the British government decided to set up the Children’s Overseas Reception Board to send children, whose parents could not afford to send them to safety, to the Dominions. They enlisted help from charities with experience of child migration, such as the Barnado’s Homes, Fairbridge Farm Schools, the Salvation Army and the Catholic Church. However the plan was not warmly received by everyone – Winston Churchil thought it was a defeatist move and others warned of the disruption it would cause to families. Nevertheless within two weeks CORB had received over 200,000 applications from parents who wanted to send their children to safety. Parents often volunteered the names of relatives or friends who would look after the children in their new country and homes were found for the others by CORB representatives or the charities.

In the first few months CORB despatched over three thousand children to the Dominions. Then tragedy struck. All shipping traffic was subject to attacks from German U-boats and on 17th September 1940, the City of Benares, sailing from Liverpool for Canada with 197 passengers on board, was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic. Ninety of the passengers were children. It was a dreadful night, with gale-force winds and driving rain; 131 of the crew and 134 passengers were killed, among them seventy CORB children. The reaction in Britain was one of horror and recrimination. It had already been suggested that it was too risky to send children overseas during the war now the sceptics had been proved correct. It was decided that no more children were to be sent to the Domninions unless their ship was in a protective convoy. As there were not enough ships to use in the convoys that meant the end of the Sea Evacuee scheme. The children had to take their chance in Britain. Unlike other child migrants, most of the sea evacuees returned to Britain once the war was over. But child migration continued until 1967 when the last nine children were sent to Australia by the Barnado’s Homes charity.

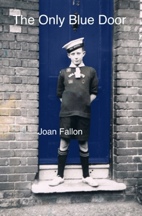

In my novel ‘The Only Blue Door’, the three children are sent to Australia under the CORB scheme in one of the last ships to take sea evacuees to the Dominions. Unlike the other CORB children they are sent from an orphanage which had taken them in, believing them to be orphans.

If you want to read more about this topic I can recommend “New Lives for Old” by Roger Kershaw and Janet Sacks, “Innocents Abroad” by Edward Stokes and Margaret Humphreys’ book “Empty Cradles”.

<a href=”http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com” target=”_blank”><img src=”http://i963.photobucket.com/albums/ae114/dr_grace423/EHFABlogbutton-2.jpg”>

Because children were young and malleable they were seen as the best category of immigrant – easy to assimilate, more adaptable and with a long working life ahead of them. The British Dominions loved them.

Something that only came to light a few years ago was the fact that thousands of children had been sent as child migrants to countries such as Australia and Canada from Britain and never knew their own parents. A social worker called Margaret Humphreys stumbled on this by accident in 1986, when a former child migrant asked her for assistance in locating her relatives. She has since formed the Child Migrant Trust and subsequently helped many people to be reunited with their families.

Throughout the late 19th century thousands of children were routinely sent out to the overseas British Dominions to start new lives, and this continued during the 20th century until as late as the 1960s. They were taken from orphanages run by religious and charitable institutions and despatched to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Some were as young as four and five; others were teenagers. Most of the children came from deprived backgrounds and it was considered to be for their own good that they were plucked from poverty and sent to a country where there was good food and new opportunities for them. The receiving countries welcomed them – they needed people and children were so much easier to mould into their way of life than adults.

So when World War II broke out in 1939 there was already a precedent for sending children abroad to start new lives. June 1940 saw the start of heavy bombing raids across London and, with the threat of an enemy invasion becoming more and more real, it was then that the British government decided to set up the Children’s Overseas Reception Board to send children, whose parents could not afford to send them to safety, to the Dominions. They enlisted help from charities with experience of child migration, such as the Barnado’s Homes, Fairbridge Farm Schools, the Salvation Army and the Catholic Church. However the plan was not warmly received by everyone – Winston Churchil thought it was a defeatist move and others warned of the disruption it would cause to families. Nevertheless within two weeks CORB had received over 200,000 applications from parents who wanted to send their children to safety. Parents often volunteered the names of relatives or friends who would look after the children in their new country and homes were found for the others by CORB representatives or the charities.

In the first few months CORB despatched over three thousand children to the Dominions. Then tragedy struck. All shipping traffic was subject to attacks from German U-boats and on 17th September 1940, the City of Benares, sailing from Liverpool for Canada with 197 passengers on board, was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic. Ninety of the passengers were children. It was a dreadful night, with gale-force winds and driving rain; 131 of the crew and 134 passengers were killed, among them seventy CORB children. The reaction in Britain was one of horror and recrimination. It had already been suggested that it was too risky to send children overseas during the war now the sceptics had been proved correct. It was decided that no more children were to be sent to the Domninions unless their ship was in a protective convoy. As there were not enough ships to use in the convoys that meant the end of the Sea Evacuee scheme. The children had to take their chance in Britain. Unlike other child migrants, most of the sea evacuees returned to Britain once the war was over. But child migration continued until 1967 when the last nine children were sent to Australia by the Barnado’s Homes charity.

In my novel ‘The Only Blue Door’, the three children are sent to Australia under the CORB scheme in one of the last ships to take sea evacuees to the Dominions. Unlike the other CORB children they are sent from an orphanage which had taken them in, believing them to be orphans.

If you want to read more about this topic I can recommend “New Lives for Old” by Roger Kershaw and Janet Sacks, “Innocents Abroad” by Edward Stokes and Margaret Humphreys’ book “Empty Cradles”.

<a href=”http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com” target=”_blank”><img src=”http://i963.photobucket.com/albums/ae114/dr_grace423/EHFABlogbutton-2.jpg”>

Recent Comments