In the second of my blogs about what it was like to be living in al-Andalus, I have invited the author John D Cressler to participate with a blog about a famous surgeon, Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi. In a time before the National Health Service and Medicare, if you became ill life could be pretty tough, but as you will see, not in medieval Islamic Spain.

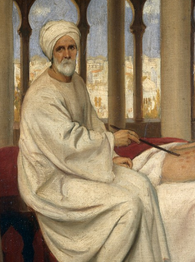

A portrait of Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi in action

A portrait of Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi in action

What comes to mind when you think of the practice of medicine in early medieval Europe, say during the late 10th century? You know, those dastardly Dark Ages! Leeches? Letting blood? Maggots run wild? Gruesome amputations using a dull, rusty blade? Biting a bullet for anesthesia? The smell of gangrene? Worse? Well, not in Islamic Spain – al-Andalus. Nope! Andalusi medicine was by far the most advanced in Europe, by a mile, and if you happened to be a knight wounded in battle, your odds of surviving that nasty sword-slash, or ugly pike-puncture of your chain mail, was far better if you were a Moor than a Christian. Why? Simple answer: Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (c. 936-1013). Known the west as Abulcasis (a corruption of the Arabic Abū al-Qāsim), al-Zahrawi was a surgeon, teacher, chemist, and royal physician to Caliph al-Hakim II. He is widely considered the father of modern surgery. Truth be told, we all owe him a debt of gratitude.

Al-Zahrawi’s is best remembered for his 30-volume (30!) encyclopedia of medicine, known as the Kitab al-Tasrif (The Method of Medicine), which profoundly influenced the practice of medicine in Europe. Completed in the year 1000 CE, the breadth of coverage was truly remarkable, and included: the design and use of a wide array of surgical instruments and techniques, neurosurgery, orthopedics, ophthalmology, pharmacology, nutrition, dentistry, childbirth, pathology, and neurological diagnosis.

The Kitab al-Tasrif’s volume on surgery was translated into Latin and became the standard source of surgical practice for the rest of Europe for the next 500 years! Al-Zahrawi specialized in curing disease by cauterization, and he invented a remarkably diverse set of surgical instruments (see the figure below), including those needed for the inspection of the interior of the urethra (ouch!), as well as for removing foreign objects from the throat, the ear, and other sensitive orifices, and even for assisting in the safe delivery of breeched-babies. If you happen to visit Córdoba, an exhibit of his instruments can be found on the Calahorra Tower Museum across the Guadalquivir River from the Great Mosque. He routinely performed surgery for the treatment of head injuries, skull fractures, spinal injuries, subdural effusions, and headaches, and gave the first clinical description of an operative procedure for hydrocephalus by surgically draining excess intracranial fluid. Who knew?!

The Kitab al-Tasrif’s volume on surgery was translated into Latin and became the standard source of surgical practice for the rest of Europe for the next 500 years! Al-Zahrawi specialized in curing disease by cauterization, and he invented a remarkably diverse set of surgical instruments (see the figure below), including those needed for the inspection of the interior of the urethra (ouch!), as well as for removing foreign objects from the throat, the ear, and other sensitive orifices, and even for assisting in the safe delivery of breeched-babies. If you happen to visit Córdoba, an exhibit of his instruments can be found on the Calahorra Tower Museum across the Guadalquivir River from the Great Mosque. He routinely performed surgery for the treatment of head injuries, skull fractures, spinal injuries, subdural effusions, and headaches, and gave the first clinical description of an operative procedure for hydrocephalus by surgically draining excess intracranial fluid. Who knew?!

An illustration of surgical instruments from Kitab al-Tasrif (credit: Wellcome Library, London)

An illustration of surgical instruments from Kitab al-Tasrif (credit: Wellcome Library, London)

Al-Zahrawi’s medical encyclopedia was the culmination of his 50-year career of medical training, teaching and practice as a physician. He vigorously advocated for the importance of a positive doctor-patient relationship, and wrote affectionately of his many students, whom he referred to as “my children.” He established and staffed dozens of hospitals in 10th century Córdoba, and emphasized the importance of treating patients irrespective of their social status, their financial means, or their heritage. He trained his students to make close observations of individual cases in order to ensure the most accurate diagnosis and the best possible treatment plan.

Not always properly credited for his massive contributions to medicine (go figure!), al-Zahrawi’s described what would later become known as “Kocher’s method” for treating a dislocated shoulder, and the “Walcher position” in obstetrics, still standard techniques in use today. He described how to ligature blood vessels (using a suture to shut off the flow of blood) almost 600 years before Ambroise Paré, and was the first to explain the hereditary nature of hemophilia.

Not always properly credited for his massive contributions to medicine (go figure!), al-Zahrawi’s described what would later become known as “Kocher’s method” for treating a dislocated shoulder, and the “Walcher position” in obstetrics, still standard techniques in use today. He described how to ligature blood vessels (using a suture to shut off the flow of blood) almost 600 years before Ambroise Paré, and was the first to explain the hereditary nature of hemophilia.

This remarkable man figures prominently in my historical novel, Shadows in the Shining City, the second book in my Anthems of al-Andalus Series. In fact, the many marvels of Islamic medicine figures prominently in all three of my novels: Emeralds of the Alhambra, Shadows, and Fortune’s Lament!

On my next blog stop, I will introduce you to another important figure in the world of medieval Anadalusi medicine: Lisan al-Din ibn al-Khatib, another deeply influential physician and polymath from 14th century Granada. Teaser: Ibn al-Khatib almost single-handedly saved Granada from the ravages of the bubonic plague sowing destruction through Europe in 1373. You know, that pesky Black Death, the scourge that killed one-third of Europe and changed the course of history. Stay tuned!

John D Cressler

Thanks John for a very informative and entertaining post. You can read more about John D Cressler and his books on his webpage http://johndcressler.com

Recent Comments